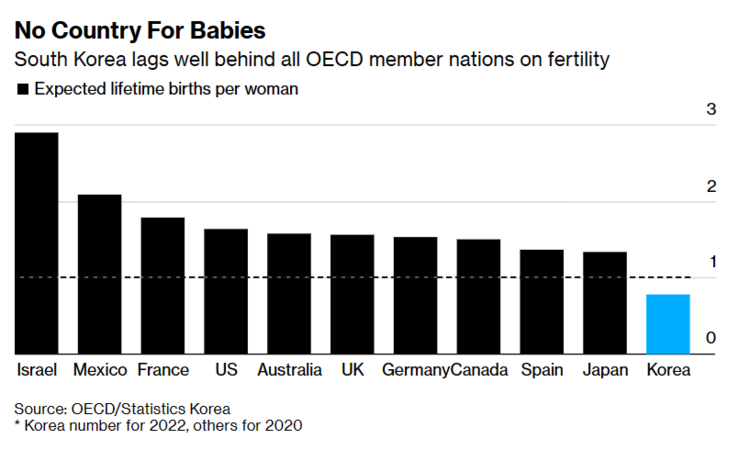

Newsnomics AJAY ANGELINA reporter | South Korea fertility rate has fallen to 0.78, counts the lowest once

again compared to other advanced countries far below 1.64 in the United States and 1.33 in Japan.

The average number of expected babies per woman of reproductive age dropped from 0.81 in 2021 to 0.78

in 2022 according to data released by the statistics office on Wednesday Feb 22,2023. That is far lower in the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries which have an average rate of 1.59.

The average age at which a woman has her first child rose to 33 last year while the number of second

children fell by 16.8%. By region, the capital Seoul had the lowest fertility rate at 0.59, while Sejong, home to

government headquarters, had the highest at 1.12, according to the statistics office.

The statistics office said, the declined number of newborns falls to 249,000 from 260,600 a year earlier. That’s

less than 5% of the population. In contrast, about 373,000 people died last year, extending what one policy

maker called a “death cross.”

The Korean people commonly blamed on economic factors that have put off the young from getting marry

and having a child – high real estate prices, the cost of education and greater economic anxiety – yet it has

proved beyond the ability of successive governments to fix, however much money is thrown at it.

The Korean government has spent 280 trillion won ($210bn) over the past 16 years to resolve the problem of falling birth rate, but has failed to turn the tide.

South Korean President, Yoon Suk Yeol, since assuming office in May 2022, and his administration has come

up with few ideas for solving the problem other than continuing in a similar vein – setting up a committee to discuss the issue and promising yet more financial support for newborns. A monthly allowance for parents

with babies up to 1-year-old will increase from the current 300,000 won to 700,000 won ($230 to $540) in

2023 and to 1 million Korean won ($770) by 2024, according to the Yoon administration.

But it proved ineffective, as many experts believe the current throw-money-at-it approach is too one-

dimensional and that what is needed instead is continuing support throughout the child’s life.

The low fertility rate carries long-term risks for the Korean economy by reducing the size of the workforce that underpins its growth and vitality.

A shrinking workforce is a major cause of Korea’s declining potential growth rate. The working-age population peaked at 37.3 million in 2020 and is set to fall by almost half by 2070, according to the Statistics Korea.